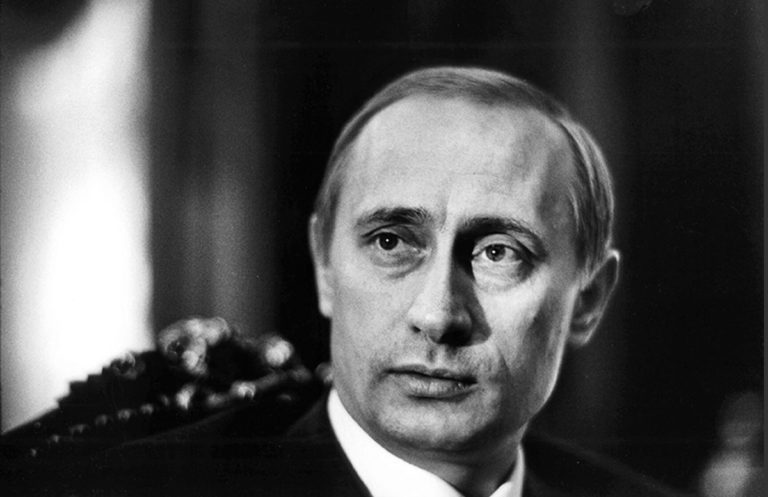

She got closer to him than any but a few Western journalists ever came: Katja Gloger, the Moscow correspondent for the German news magazine Stern, travelled and met with Russia’s President Vladimir Putin many times over the course of several months in the early 2000s. In his home, on fishing trips or during sports activities, and in his Kremlin office; his tendency to keep people waiting, sometimes for hours, was already evident back then. He spoke of democracy, the market economy, and reforms. Twenty years later: a personal retrospective.

Russia is by no means Putin. This vast country encompasses so much more than him. And yet – Putin is Russia. He embodies the collective experience and yearnings of this post-Soviet society in a way almost no one else could. In the 20 years of his rule, he has put the stamp of power on this country and its people in a way almost no one else has: the stamp of his power, in pursuit of a historic mission, as he once told me. As though the vision of Vyacheslav Volodin, his former chief of staff, absurd though it sounds, were coming true: “As long as there is Putin, there will be Russia. No Putin – no Russia.”

It would be hard to find words that convey more succinctly the essence of Putinism, the triumph and also the tragedy of a system of power that revolves around this one man.

“No Putin – no Russia“

Moscow, in the spring of 2002. We sprawl in armchairs, their cushions far too soft, waiting, as everyone does, sometimes for hours. This is in the early years of his presidency, he allows journalists to get fairly close, or appears to anyway. We – Konrad R. Müller, the famous photographer of chancellors, and I – are the first Western journalists allowed to accompany him, on several occasions, over the course of months: while travelling, while fishing in the Volga delta, at his home while he is doing his morning sports, in his Kremlin office, and at international summit meetings.

Even in those days, he was almost always late. Why? No one knows exactly. Perhaps simply because he could: he could get away with making everyone wait. Because the new Russian world – and not only it – had already begun to revolve around him.

He has invited us to his home, his Novo Ogaryovo residence on the Rublyovka outside of Moscow. Two imposing, brick buildings, beige, with vaulted rooves and suggestions of turrets and battlements, set in an immaculate park by the Moskva River. When he finally arrives, he pours tea and spreads butter and caviar on small slices of bread, an attentive, charming host. He enjoys speaking his quiet, refined German. He is a private person – and at the same time, of course, not private at all. But he permits the conversation to turn to Russia’s future, to democracy and reforms, to his historic mission to establish a new Russian statehood. It all sounds so … Western: “I want a real market economy. I want Russia to have a real multiparty system.”

The conversations are long, he explains things in detail and yet: something feels a bit off. It’s as though he were following an unerring instinct telling him what it is that we – perhaps – want to hear.

Seen from the outside, Putin’s rise to the presidency of the Russian Federation in ten short years amounts almost to a miracle. But there were many miracles in Russia in those ten years following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the ‚wild ‘90s‘ so traumatic for so many people in Russia. People became billionaires overnight. Just like that, the old Party nomenklatura declared themselves to be democrats and plundered the entire country. His network, his loyal service, as discreet as it was efficient, and his German language skills were invaluable resources, first in the Petersburg city administration, then in the property management department of the Kremlin, next as the director of the FSB, the KGB’s successor agency, and finally, as the prime minister and designated successor of Boris Yeltsin, already suffering from heart disease and the effects of heaving drinking. “He was,” in Yeltsin’s characterisation of him, “steadfast in a military way.“

Was he proud of his native land, the Soviet Union, I asked him once, after he had already become president. “No, unfortunately not”, was his answer. “We always led such …“, he searched for the German word he wanted, “… degrading lives.“

Rough sketches of an unusual ascent

An outline, hardly more, rough sketches of what was, in every respect, an unusual rise to power. A long-desired child, born seven years after the victory in the Great Patriotic War, in Leningrad, the city so traumatised by the Germans’ systematic starvation blockade. A million dead, a wretched death from hunger or the cold; victims in every family, including his own. The survivors had learned not to speak the truth of what they had endured.

A boy grows up, like millions of Soviet children of his generation, living with his parents in one small room in a communal flat. Three families share the kommunalka on the fourth floor at no. 12, Baskov Lane; a makeshift kitchen in the hallway, no running water, rats scurrying in the stairwell.

Fleeing the kommunalka’s noisy confinement, the boy escapes to the streets and courtyards of his district, where the bigger boys make the rules. ‚Putka‘, they call him, this slender boy. He curses like he is supposed to and fights like the big boys, and endures insults from no one. Always show strength – it doesn’t matter if you are in the right. “Because the weak”, Vladimir Putin would say later, “get beaten.”

A child, obviously underchallenged and overactive, hardly able to sit still during lessons at school. He crawls under the bench, jumps up from his seat constantly, throws the blackboard erasers. Vera Gurevitch, his teacher back then, told me that he once ran out onto the balcony in front of the fourth-floor classroom, hung from the railing and pulled himself, hand over hand, from one window to the next. Evidently, the boy knew no fear or had little instinct for danger.

Sambo, then a new form of martial art, a mix of karate and judo, gives him a place to channel his restless energy. The hard training in the competitive team, the peer pressure and the trainer, whom he admires, teach him discipline and patience, to control his emotions and that reserved concentration he has, which can seem like he’s lying in wait.

He’s a teenager dreaming of the adventurous life of a secret agent, probably influenced by the television series, so popular in those days, about KGB spies who battled the Nazis, the Soviet versions of 007. One day he knocks on the imposing doors of the Leningrad KGB headquarters, the ‚Big House‘, to apply to the secret service so feared by his fellow

citizens, this weapon of terror and dictatorship, one most people are anxious to avoid. However, Vladimir Putin studied law, to improve his admission prospects.

His first foreign posting as a young KGB officer is in 1985. Now a part of an elite organisation, the ’shield and sword‘ of the Party, he comes to Dresden in the GDR, which is more an outpost than anything else. It is probably more office work than spy adventure that awaits the operative agent there. His German friends are mostly colleagues, Stasi officers. What is happening in his homeland in these years must seem strange and remote to him: General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and his charm offensive in the West; glasnost and perestroika, the high hopes and the dynamism of a new beginning. The feeling that comes when one ceases to fear those with power – and senses freedom is near.

What Comrade Putin experienced in the winter of 1989 was very different, indeed, a ‚paralysis of power‘ he would call it later. The system that he had loyally served betrayed him. He had a life-changing experience, as he tells it, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall. 6 December 1989, Dresden residents began to gather in front of the KGB office, demanding entry. Putin’s request for help from the Soviet military commander goes unanswered. “Moscow is silent.” And although the demonstrators eventually dispersed peacefully, it is clear that for Vladimir Putin this day came to symbolise a capitulation, one that the Moscow leadership brought upon itself through its own incompetence: “They simply threw in the towel and left. All our work had been for nothing.“

Later, he asks to revisit the question of whether he was proud of the Soviet Union: “No, not everything was bad,” he says then, “but at the same time, there was always something wrong in our lives.”

Guarantor of a deceptive stability

Nearly 20 years after this conversation, there is an entire Generation Putin who knows only him, ‚VVP‘, as president and, yes, de facto tsar, the guarantor of a deceptive stability and a bulwark against chaos like that in the 1990s. Back then, when people lost their jobs and their savings overnight and, in a way, their identity as well. When suddenly nothing remained of Soviet life, of all the heroes and victims, but humiliation and a fear of the future. Some of those who were to blame were in … the West; but in the West, the longing for the restoration of imperial greatness and the penchant for conspiracy theories that came with it were underestimated to an extent verging on the criminal for years.

What people in the West failed to understand for too long: Vladimir Putin is not the exception on the Russian political scene and certainly not the ‚German‘ in the Kremlin. If anyone, Mikhail Gorbachev was the exception.

In our conversations, Putin touted Russia as a democratic country, ostensibly his vision for it. However, he evidently had little understanding of the mechanisms of democratic societies. To him, they appeared worthy of neither imitation nor emulation.

He does identify Russia as a European country – albeit one that is also a unique great power, a sovereign Orthodox civilisation. An exceptional power, like the USA and China, with the drive to shape global affairs, and soon the power to do so as well.

It is safe to say that Vladimir Putin achieved an enormous amount, the aims set out in his Millennium Message at the end of 1999. The self-declared gosudarstvennik succeeded in restoring the de-facto omnipotence of the state – which is to say, of the president.

He used old Soviet structures and mentality to establish the vertical of power. To do so he had to gain control over the mass media, which he achieved within only a year. Establishing an independent judiciary was never part of the plan. Instead, he turned the country into a giant laboratory. The objective of the experiment: to develop a modern authoritarian system, with ‚manual steering‘, a pseudo-democratic parliament incorporating systemic opposition, and elections subject to manipulation. And now he is building a surveillance state, very much along Chinese lines: the camera installations in Moscow alone will soon number in the hundreds of thousands. The increasing control over the internet is part of this project, as is the selective use of harsh repressive measures. The circa 300,000 members of the National Guard [created in 2016] are under his authority. Civil society is ultimately subject to the mercy of the Kremlin. The system does leave some niches and spaces open for smaller, independent media and NGOs, sometimes even for criticism and limited street protest. Those who wish to do so, can leave the country. And freedom? “The ruling classes usually talk about freedom to pull the wool over the eyes of those whom they govern”, Putin once explained.

Putin got rid of the Yeltsin elite – 10 years at a labour camp for Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the oil billionaire with political ambitions, making room for new members of a powerful elite, the toxic blend of secret service officials at the ministerial level, well-trained technocrats, smart big business leaders and business bureaucrats. This clan of Putin oligarchs has been building a system of mutual surveillance and competition, one that resembles a parasitic mafia state to the minds of critics; and now their sons are taking over the business. They control access to the country’s key resources, to the oil and the natural gas and the Baltic pipelines, to the military-industrial complex and the state-owned banks; they, too, prefer offshore private accounts – and just in case, there’s always that Western passport tucked away somewhere. He, the president, moderates and exploits conflicts.

United in the ‚Putin consensus‘

And yet: for almost a decade Vladimir Putin gave people stability and hope for the future. The economy grew, jobs were created, wages were paid. The oil price shot up five-fold over these years, and oil and natural gas production along with it. The state and the elite raked in billions of dollars in windfall profits, and some of them were distributed around the country. United in the Putin consensus, people attained a modest level of prosperity; they consumed, and the promised golden years seemed to have arrived.

Probably his greatest opportunity in this first Putin decade was to pave the way for the societal modernisation and democratisation of his deeply wounded country at last, the arduous challenge facing his generation. Even in the West people were pinning their hopes on him and a ‚modernisation partnership‘, above all with Germany. It was an opportunity he did not take.

As the years went by, he grew firmer in this decision, and, to be honest, the political elites in the West provided him with enough reasons to do so. Their internal conflicts and the cynical double standards of the leading hegemonic power, the USA, the self-declared victor of the Cold War; the war in Iraq and the global crisis brought about by the greed of the financial elites; ultimately, the supposedly decadent Western values, the alleged moral corruption – no, Russia would not join the ranks of this civilised West. What’s more, it would certainly not bow down to it.

Democracy, market economy, reforms? Had he ever really believed in those things? The word is that he was shaken by the demonstrations of the urban middle class against the obviously fraudulent Duma elections in 2011 and the protests against him in 2012; this, too, was probably a life-changing moment. His response: brutal intimidation and repression. He is said to have interpreted the peaceful revolt against the corrupt system as an attempt by the USA to instigate another colour revolution, this time in front of the gates of Moscow’s Kremlin and orchestrated, it was said, by Hillary Clinton personally.

And then there was the shaky mobile phone footage of the wretched demise of the Libyan dictator Muammar al-Gaddafi, who was killed after being dragged from a drainage pipe by his triumphant adversaries after the NATO intervention in Libya (granted de facto legitimacy by Russia’s abstention in the UN Security Council vote). It is said that, for Putin and the men around him, this was yet further proof of the bloody chaos the West had to answer for. Better a Russia lonely and alone, a sovereign fortress defending against the liberal order, than that alternative.

“Russia leaves the West“, announced Dmitri Trenin, now director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, back in 2006. Very few took any notice of Russia’s incipient ‚detachment‘, the growing alienation. Putin’s plain language at the Munich Security Conference in 2007 rang in the geopolitical repositioning of Russia. Integrating the great-power Russia into the European security structures of the 1975 Helsinki Accords or the 1990 Paris Charter was no longer an option anyway – if it ever had been.

The claim to a ‚zone of privileged interests‘ in the post-Soviet space manifested itself quickly, though, in Georgia in 2008 and, only a few years later, with the annexation of Crimea and the attempt to create a sort of Moscow protectorate in eastern Ukraine. The Donbas: a smouldering de facto war that has already killed 13,000 people and turned another two million into refugees.

More than anything else, the hurried second round of NATO expansion eastward counts as a major strategic miscalculation on the part of Western politicians with respect to Russia. Here again, the president showed himself to be ‚Russia’s Putin‘ through and through, in the words of political scientists Samuel Greene and Graeme Robertson. NATO’s supposed advance towards Moscow shook the foundations of a society blighted for decades, that had been forced to find its identity primarily in heroic and self-sacrificing defence against the enemies from the West, shaped by a victory over German fascism in the Great Patriotic War, won at an unthinkable cost, 27 million dead. Conversely however, the fixation on the supposed threat of NATO expansion gave rise to one of the ‚fundamental errors‘ of Russian foreign policy, as Dmitri Trenin put it: “The rebirth of this image [of Russia as the military adversary of the West] a quarter of a century after the end of the Cold War is a strategic defeat for Russia.”

Geopolitical zero-sum gamer

Today, Putin’s Russia is gaining traction in a multipolar world, the post-West world order. It has seized the right of veto over the restructuring of the global order – and that is certainly something, considering it is an increasingly militarised country with a gross domestic product only a bit larger than Spain’s.

With ruthless opportunism, the geopolitical zero-sum gamer advances into every area from which the USA, the West, is withdrawing – as if Russia’s renewal could only be won at the cost of others, and against others.

At once both sovereign and solitary, Putin’s Russia projects its political and military power anywhere that space opens up, in the Middle East, in Syria, Libya, Turkey, and increasingly, in South America and resource-rich Africa as well. With smooth virtuosity, the clever Russian diplomats interpret international law in accordance with their current interests. Cynicism, you might call it – or geopolitics. It is no accident that mainly dictators and authoritarian regimes are the recipients of the support with hardware and software, with weapons and mercenaries, with bribery and social media trolls. Needless to say, violence is also considered a legitimate policy tool – as in Syria, for example, which is currently undergoing relentless bombing by Russian combat jets (and Iran-backed groups) during a supposed peace under Assad.

Both sovereign and solitary at once

Thus, the Russian president is rising to the status of a top player in the global power-politics game, establishing Russia as, yes, a new hegemonic power (Ordnungsmacht). Within an international alliance of ’sovereign great powers‘, Russia negotiates, representing the interests of a small powerful elite, forming alliances that are as flexible as they are fragile, in which the rule of the gun takes precedence over the rule of law. And it is growing: a global order of the unscrupulous.

However, the people of his country are paying a heavy price for this restoration, one that makes itself felt daily. This includes zastoy, the new stagnation, an absence of growth, despite all the exhortations and national projects; the demographic crisis, the increasingly empty countryside; the appalling social inequality and cynical acceptance of corruption in what is actually a very rich country; then, too, the queasy feeling that once again, the people have been robbed of their future. The Crimea consensus, once charged with imperial-patriotic enthusiasm through aggressive propaganda and fake news, has begun to crumble; many seem simply weary of the permanent crisis over Ukraine. So many younger people, people who have travelled and surf the web defying all censor legislation; they have little hope for change. But they want to be more than just divannye kritiki, couch critics. Many dream of leaving their country bound for the West, and still others are losing their fear.

In the 21st year of his rule, Vladimir Putin is the prisoner of his own omnipotence, they say, a man with enormous power who does not want to step down, who perhaps cannot step down, and is therefore having a new constitution drawn up – his constitution, it, too, part of the alarmingly perfectly choreographed Russian enactment of what they call the sovereign democracy. With it, he, VVP, may become the de-facto president-for-life. This, too, bodes ill for the future of his country.

“Russia is destiny”, he said once. Just as he, eternally young even then, declared himself to be Russia’s destiny. Will they really be raising monuments to him someday in the distant future?