Vladimir Putin seems to have merged with the Russian presidency. He has even admitted this himself in his speech to the State Duma plenary session on 10 March 2020: „I am convinced that a time will come when the supreme power in Russia, that of the President, will no longer be personified and will no longer be associated with a specific person“ (kremlin.ru 2020) . However, he left open the question of when that time will come. Russia still has to go through a long, evolutionary development, for which a strong presidential hierarchy of power is absolutely indispensable, in Putin’s opinion. In March 2020, the president initiated a process that would allow him to remain in office after 2024 when his current constitutional term ends. He launched a constitutional amendment process making it possible to annul his previous terms in office so that he can serve two more, potentially extending his rule to 2036. Is it possible to conceive of the institution of the presidency being separate from Putin? What system of power has Putin built over the past 20 years? And finally, how much does Putin control in Russia today?

The question of how long Putin will remain in power has been at the top of the agenda of Russia watchers for quite some time. After two decades as head of state and interim head of government, Putin announced a constitutional reform in January 2020. His announcement not only marked the most far-reaching overhaul of the Constitution since its adoption in December 1993, it also paves the way for him to run for a fifth term in 2024 by annulling his previous terms. After so many years in power, the question arises: to what extent does Putin personify the Russian political system?

Does Putin decide everything himself?

Many observers claim that Putin alone controls the political process in Russia. A more accurate conception, however, is that we are dealing with a „double state“ in Russia. In this state, there are two different regimes whose interaction creates constant tension and uncertainty. One regime is that of the president’s „manual control,“ in which his personal authority is paramount. The second regime is governed by regular and rule-based patterns of behaviour, for example in the administration of the state, in which even the strong president cannot easily interfere.

Yeltsin was already called an “electoral monarch” because of his personalistic style (Shevtsova 2007) . However, personalisation has steadily increased under Putin. A growing number of policies that were once part of the second regime are no longer protected from attacks by the first regime (Baturo/Elkink 2016 ). Of course, this rules-based, institutionalized behaviour should not be confused with „democracy“ or good governance: even under Stalinism such a second regime existed to a certain extent (Gorlizki 2002) .

Putin as the mafia boss of a network state?

To describe the Putin system, one can imagine a kind of solar system in which various actors from the political and economic elite orbit the Putin sun. The celestial bodies are of different weights, are closer to the sun or further away from it and can also have their own satellites. Other metaphors can also be used: a politburo in which there are different categories of members according to the Soviet model, or several Kremlin towers that face each other in contention. One of the most elaborate models is that of sistema: a network state in which the elite bends or bypasses laws (Ledeneva 2013) . The network state creates interdependencies in the extremely complex network of relationships among this elite.

However, it would be too simplistic to reduce the sistema to a kleptocracy, a mafia state, or a militocracy under the sole rule of the siloviki, the leaders of Russia’s military and intelligence agencies. Informal practices remain ambiguous, moving smoothly between legality and illegality, legitimacy and illegitimacy. For example, someone in the presidential administration can pick up the phone to influence the courts (telephone justice). On the other hand, governors sometimes make calls to overcome bureaucratic hurdles in building factories, or to call back aggressive regulators from successful companies. The new prime minister, Mikhail Mishustin, for example, succeeded in modernizing the tax authority. He is considered a comparatively effective manager in the civil service, who in 2020 received the second most important post in the country. At the same time, he amassed a significant fortune with the help of his family members, according to Alexey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation.

Organisation chart of power

What is Putin’s place in the sistema? In the network state, not only personal, but also predominantly formal, competences play a prominent role. These signal to the individual actors of the elite who is the most powerful patron of the network. Because of his position as head of state, Putin is the linchpin of this patronal presidentialism (Hale 2014) . He is at the forefront of various pyramid-shaped networks and thus acts as a referee in the struggle for power and resources in the state and economy.

Vladimir Putin inherited from Boris Yeltsin a 1993 constitution in which the presidency was endowed with enormous powers, especially by international standards. The powers are distributed among different state bodies, but the president is hardly ensnared by checks and balances. Instead, he hovers over the other branches of government and has the final say, especially with regard to Parliament.

Although with a few exceptions the Constitution remained virtually untouched until 2020, the president’s powers have been steadily expanded beyond its original stipulations since 1993. The result is an institutionalised asymmetry of power in which the president and the executive branch play a much greater role than any other branch (Burkhardt 2017) . The entire political system was affected, from parliament and parties to elections, courts, federalism, state administration, civil society and the media.

All just „virtual politics“?

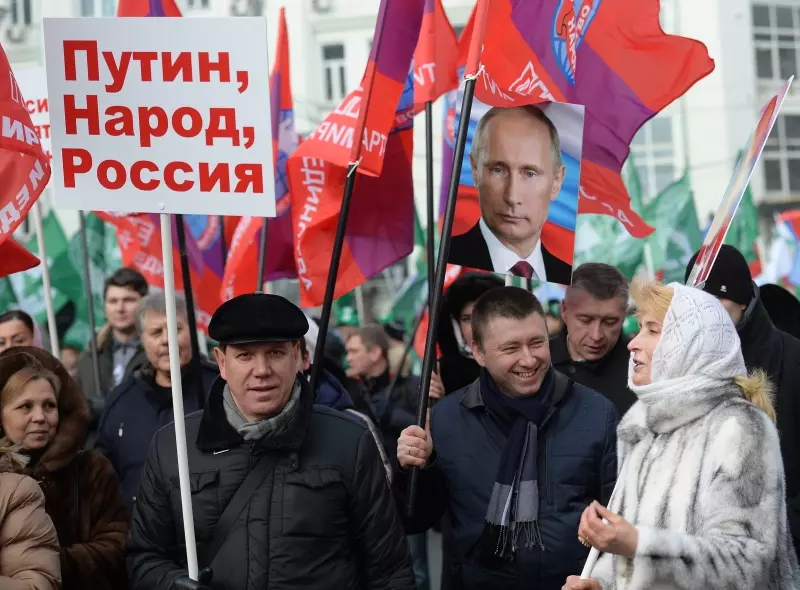

While in the 2000s many observers argued that formally democratic institutions such as parties, parliament, or even elections in Russia under Putin were simply „virtual politics“ (Wilson 2005) or made for propaganda, a new realisation has emerged in recent years: political institutions function differently than in democracies, but they still perform important roles. Elections in Russia, for example, are not free and fair, since the campaigns are distorted and undemocratic. However, elections are not meaningless: first off, they should co-opt elites and the opposition as well as provide information about how much popular support the regime has. Additionally, lopsided election results for Putin and United Russia are designed to send signals of strength and used to command the loyalty of regional bureaucrats (Zavadskaya et al. 2017) . The same applies to the so-called „party of power“, the ruling party of United Russia: Despite its poor public image, the party guarantees the internal cohesion of the elites through its dominant position in the Federal Assembly, among governors, in regional parliaments and among mayors, and serves as a warning system to bring disloyal behaviour or counter-mobilisation among the elite to light early on.

However, excessive centralisation can be costly. Already at the beginning of his first term, Putin pushed for harmonising federal and regional legislation, strengthened control over regional security agencies by establishing federal districts, abolished the 2004 gubernatorial elections, deprived the regions of significant tax revenues through a complicated redistribution system, and thus increased fiscal control. However, this centralisation did not lead to better policy outcomes; rather, it is one of the reasons for Russia’s bad governance (Gel’man/Zavadskaya 2020) . Governance problems, lack of feedback mechanisms and misincentives for the regions prevent the socio-economic objectives set in the May 2012 presidential decrees and the 2018 national projects from being achieved. Although there are individual „pockets of efficiency“ (Gel’man 2018) in federal and regional civil administration, the institutionalized power asymmetries lead to a paradox of power: the omnipotent president, who can intervene in all policy areas through manual control, is also powerless when it comes to day-to-day management and long-term goals.

How popular is Putin?

The Kremlin likes to measure Putin’s popularity in polls, and there is good reason for doing so. In fact, the presidential rating is one of the most important resources available to Putin. His consistently high approval ratings have hovered between 60 and almost 90 percent over the past 20 years, symbolizing the leader’s direct engagement with the people. To maintain the „image of invincibility“ and the sense that there is no alternative, the Kremlin must ensure that Putin is the most popular politician in Russia permanently and by far (Magaloni 2006) . As constant plebiscites of approval, ratings and polls are intended to replace other broken feedback channels to the population, such as elections or the media (Yudin 2019) . Even for governors in the regions, they are considered one of the most important indicators that determine their careers (Reuter/Robertson 2012) .

But what makes Putin popular, and to what extent is this popularity real? In particular, the fluctuations in confidence and approval ratings show that it is not so much Putin’s biography and personal traits that contribute to his popularity, but above all two aspects: the perception of economic development and the expectation that one’s own economic situation will improve, and, in the foreign policy sphere, the sense of an external danger.

Large fluctuations after unpopular social or pension reforms or longer-term downward trends after the 2008 global financial crisis reflect changing perceptions among the population (Treisman 2011) . Russian foreign policy sometimes causes erratic changes: especially in conflict situations in which Russia is threatened, or to the contrary, when foreign policy successes, such as the annexation of Crimea, trigger euphoria, there are rally-round-the-flag effects that at least temporarily increase support for Putin (Frye 2019) .

However, media control and Internet censorship play a crucial role. One simulation assumes that a repeal of Internet censorship would cause Putin’s rating to plummet by 35 percentage points (Guriev/Treisman 2015) . The question of whether Putin’s popularity is genuine is therefore not clear. In any case, research shows that respondents do not lie when asked about Putin (Frye et al. 2017) . The restriction of political competition, censorship of television and Internet control create an alternative reality, which suggests majority support for the president (Volkov 2020) . Since most Russians are above all apolitical, the minority, which is willing to answer questions from pollsters, often joins the perceived majority for social reasons (Greene/Robertson 2017) .

Putinism as ideology?

Especially after the annexation of Crimea, the debate about the role of ideology in Russia flared up again. For example, Masha Gessen saw Russia on the road to totalitarianism, and Timothy Snyder even diagnosed the dawn of fascism (Gessen 2017 , Laruelle 2018) . Although some elements of totalitarianism, such as ideologically driven state propaganda or high approval ratings for Putin, were present in the first period after the annexation as a sign of mass mobilisation, developments during the following years showed that Russian society is moving in exactly the opposite direction: the overly clumsy state television is becoming more unpopular, and especially after the 2018 pension increase, approval ratings also fell back to pre-2014 levels.

Not only did the population struggle to mobilise for Putinism, but in many places, local networks of activists have begun mobilising against the regime because of declining real incomes, environmental problems, or election manipulation. That is why politics in post-Soviet Russia is largely non-ideological. For most actors in the state, it can even be dangerous to position themselves ideologically. This is due to the fact that ideological commitment would require a long-term planning horizon, which even the most important members of the elite have only limited access to.

However, this does not mean ideological factors are completely arbitrary or play no role at all. In an elaborate attempt to crack the code of Putinism, the American political scientist Brian Taylor reduces it to the following three elements: ideas, behaviours, and emotions (Taylor 2018) . Among the guiding ideas are a strong state and great power status, an anti-Western and anti-American stance, as well as conservatism and anti-liberalism. As behaviours, the „collective Putin“ prefers control, order, unity and antipluralism, loyalty and hypermasculinity. Emotionally, respect and humiliation, resentment as well as vulnerability and fear are of great importance. Taylor, however, warns against a too one-dimensional view of this interpretation of Putinism: some elements were already present in Russia before Putin came to power. And, although these elements are shared by a significant part of the elite and wider society, factors such as generational change or the modernisation of society from below contribute to Putin’s life constantly rewriting the already incoherent code of Putinism (Panejach 2018) .

The question of power and the Medvedev experiment

The question of whether Putin should be separated from the institution of the president poses challenges to Putin himself. To at least preserve the appearance of legality, he launched a kind of natural experiment between 2008 and 2012. He resigned because of the presidency’s two consecutive term limit. His successor, Dimitri Medvedev, was elected president, and Putin formally held the second most important post in the Russian state as prime minister – but in reality, remained the most important man in the state. This constellation is called rokirovka or castling and represents an almost ideal research design from a social science point of view.

The aim of the experiment was to find out whether it was enough to remain in power de facto. If Putin’s power were to be pinned solely to his person and networks, then, counterfactually, nothing should have changed in these four years, even if the prime minister has far fewer institutional levers than the president. It is not known whether Putin and Medvedev had agreed in advance, and to what extent their differing preferences in domestic and foreign policy in the tandem were just a show. The experiment, however, demonstrated – at least as Putin understood it – that it was not enough to remain in power defacto: in order to continue the Putin system in the long run, Putin also needed the formal and symbolic power of the strong presidency. In the spring of 2020, Putin has created all the conditions for this.